How Were Japanese Fine Arts Different From the Chinese Models?

- Annotation

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Wood identification of Japanese and Chinese wooden statues owned past the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA

Journal of Wood Scientific discipline volume 68, Article number:11 (2022) Cite this article

Abstract

Precious cultural assets of E Asia are constitute worldwide and hold many important art-historical meanings, for example Buddhist statues. In this study, nosotros conducted wood identification of Japanese and Chinese statues owned by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA. From the 8 Japanese wood sculptures and one Chinese sculpture, 15 samples were collected. The anatomical features of these 15 samples were scrutinized using synchrotron Ten-ray microtomography or conventional optical microscopy. The results showed that the eight Japanese statues were fabricated from Chamaecyparis obtusa, except for the base of operations of one Japanese statue that was made from Cryptomeria japonica. Both species are important conifers in Japan. In dissimilarity, the Chinese statue was made from hardwood, Paulownia sp.

Introduction

In Japan, woods identification of wooden statues from the eighth century AD has been conducted jointly by art historians and wood anatomists. Recently, it was hypothesized that the selection of Torreya nucifera for the eighth-century statues in Japan refers to an ancient sacred text that mentions the usage of forest species for statues. The text mentioned that "Apply Santalum spp. for making Buddhist statues, but if yous do not take it, use haku." This sacred text might take been brought to Japan with the arrival of the Chinese monk Ganjin in 753 Advert (Ch. Jianzhen; 688–763) [1,2,3]. Santalum spp. was introduced to Communist china from India, and the usage of "haku" was proposed equally a substitute of Santalum spp. in People's republic of china. Furthermore, recent investigations revealed that when this concept of using substitute wood species for statues was introduced to Nihon, Torreya nucifera was selected as "haku". In terms of woods selection, it has been suggested that the species of wood used for statues in neighboring countries of Nippon, such equally Communist china and Korea, tin can help reveal the origin and propagation of Buddhist statues.

Many Japanese and Chinese cultural properties of loftier academic value are stored and managed in museums in Europe and the United States. At that place are diverse reasons and circumstances regarding why many of these outstanding cultural assets are located overseas. For example, in Japan, many outstanding Buddhist statues were sold to foreign countries due to historical events, such equally the anti-Buddhist move at the beginning of the Meiji era (haibutsu kishaku), which involved the destruction of Buddhist temples, images, and texts during the Meiji era (1868–1912). Moreover, many of China'due south fantabulous Buddhist statues are now displayed in museums in Europe and the United States, and not many remain in China.

Dissimilar in Japan, few surveys have been conducted on the wood species of these wooden statues in strange countries. Recently, our group has investigated many outstanding East Asian statues preserved in foreign countries and examined the wood species of wooden statues [4,five,6,7,8,9,x], and the information on these in East Asian countries are gradually accumulating. Regarding Chinese Buddhist sculptures, wood belonging to the genera Paulownia, Salix, Tilia, Populus, Santalum, Juniperus, and Cupressus are used [4,5,6]. Thus, although the amount of data remain limited, recently we were able to conduct a survey in the Cleveland Museum of Fine art of wooden statues from the Tang Dynasty that have not survived in China [xi]. We believe that it is important to share these data with researchers in various interdisciplinary fields and those involved in restoration.

In 2019, we had the valuable opportunity to conduct a survey of the woods species of sculptures from Japan and People's republic of china stored in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The museum has a large collection of Japanese heritage sculptures. Nowadays many Due east Asian cultural properties exist in museums in Europe and the U.s., which have been studied from an art-historical perspective, simply some of those have not been scientifically investigated. Therefore, this projection aimed to survey and create a database of these woods species together with cultural properties in Japan.

In this study, we primarily identified forest species of these forest statues using a microscope. Withal, depending on the degradation state and size of the samples, the synchrotron Ten-ray microtomography (SRX-ray μCT) method [12,13,xiv] was also applied.

Materials and methods

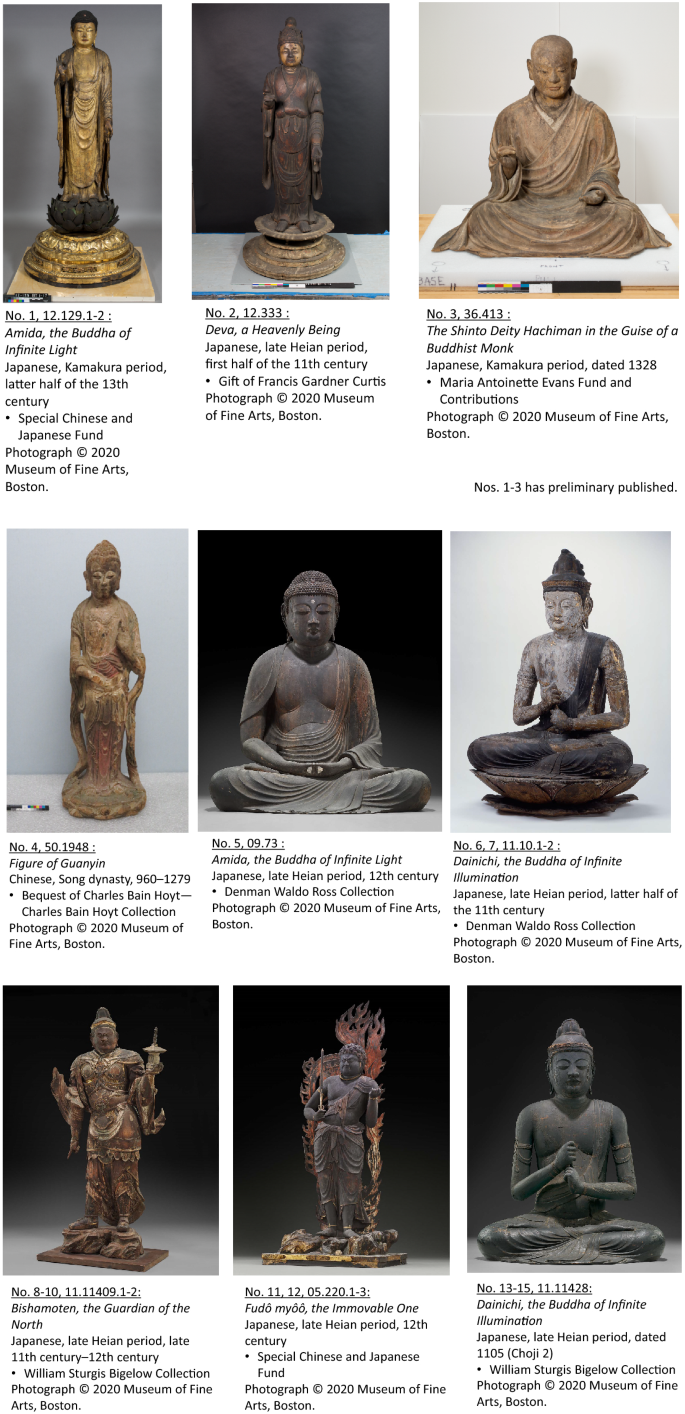

In this report, woods identification was performed on 15 samples obtained from eight Japanese sculptures and one Chinese sculpture in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA (Fig. 1). Forest identification results of Nos. i–3 have been preliminarily reported [7]. Still, since information technology would be useful for several researchers to study the accumulated results of the survey at the Museum of Fine Arts, the results are listed together hither. Regarding the Japanese statues, seven of the eight Japanese Buddha statues were created using the yosegi technique (joined wood block construction). These wooden statues were fabricated from various parts of the forest blocks, and we did not survey all the private pieces. Indeed, some may accept been added during the restoration. Notwithstanding, in this survey, the conservator in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, could confirm the original woods and collect the samples. Thus, these concerns can exist dispelled to some extent.

Photographs of i Chinese statue (figure of Guanyin) and eight Japanese statues (the remaining 8). These statues are found in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, of which Nos. 1–iii have already been published in a previous report [seven] and are listed for reference

The details of the samples are described below:

No. ane in Table ane, CON428755. Object data for 12.129.i-2 [seven].

Amida, the Buddha of Infinite Light.

Japanese, Kamakura catamenia, latter half of the thirteenth century.

Wood with golden and inlaid crystal; joined woodblock structure.

*Special Chinese and Japanese funds.

No. 2 in Tabular array 1, CON437281. Object information for 12.333: [vii].

Deva, a Heavenly Being.

Japanese, late Heian menses, start half of the eleventh century.

Wood with polychrome and lacquer; single woodblock construction.

*Gift of Francis Gardner Curtis.

No. three in Tabular array i, CON437903. Object information for 36.413: [7].

The Shinto Deity Hachiman in the Guise of a Buddhist Monk.

Japanese, Kamakura menstruation, dated 1328.

Wood with polychrome and inlaid crystal; joined woodblock construction.

*Maria Antoinette Evans Fund and Contributions.

No. 4 in Tabular array i, CON438001, CON437997. Object information for 50.1948:

Effigy of Guanyin.

Chinese, Song dynasty, 960–1279.

Wood.

*Bequest of Charles Bain Hoyt—Charles Bain Hoyt Drove.

No. 5 in Table ane, SC168748. Object information for 09.73:

Amida, the Buddha of Infinite Light.

Japanese, late Heian period, twelfth century.

Wood with gold; joined woodblock structure.

*Denman Waldo Ross Collection.

No. six, 7 in Table one, E9184CR-d1. Object data for 11.10.i-ii.

Dainichi, the Buddha of Space Illumination.

Japanese, late Heian menstruum, latter half of the eleventh century.

Wood; joined woodblock structure.

*Denman Waldo Ross Collection.

No. 8–ten in Table 1, SC168755. Object information for eleven.11409.1-2:

Bishamoten, the Guardian of the North.

Japanese, late Heian period, late eleventh–twelfth century.

Wood with polychrome and gold; joined woodblock structure.

*William Sturgis Bigelow Collection.

No. 11, 12 in Tabular array 1, SC168744. Object information for 05.220.1-iii:

Fudô myôô, the Immovable Ane.

Japanese, belatedly Heian menses, twelfth century.

Wood with polychrome and gold; joined woodblock structure.

*Special Chinese and Japanese funds.

No. thirteen–fifteen in Table 1, SC168757. Object information for 11.11428:

Dainichi, the Buddha of Infinite Illumination.

Japanese, belatedly Heian catamenia, dated 1105 (Choji two).

Wood with gold; dissever-and-joined construction.

*William Sturgis Bigelow Collection.

Samples shaped and sized like the tip of a toothpick were carefully taken from cracks and naturally occurring hollowing on the underside of the sculptures with the consultation of the curators and conservators, without harming the surface and appearance of statues. The details of the samples are listed in Table 1. Each preparation for the identification of wood samples was conducted at RISH, Kyoto University, Japan. Nigh of the samples were soaked in water for softening. To set up the microscopic slides, thin sections were taken using razor blades from transverse, radial, and tangential surfaces (approximately xv–30 µm thick). The sections were placed on glass slides and mounted in a mixture of ethanol and glycerol. The sections on the drinking glass slides were heated on a hot plate at a temperature college than 100 °C to remove air bubbles from the woods sections. Afterward heating, the sections were rinsed with fresh water and mounted in mounting media containing a mixture of Arabic gum and chloral hydrate.

The slides were examined under an optical microscope (Olympus model BX51, Japan), and each micrograph was captured using a digital camera (Olympus model DP70, Japan).

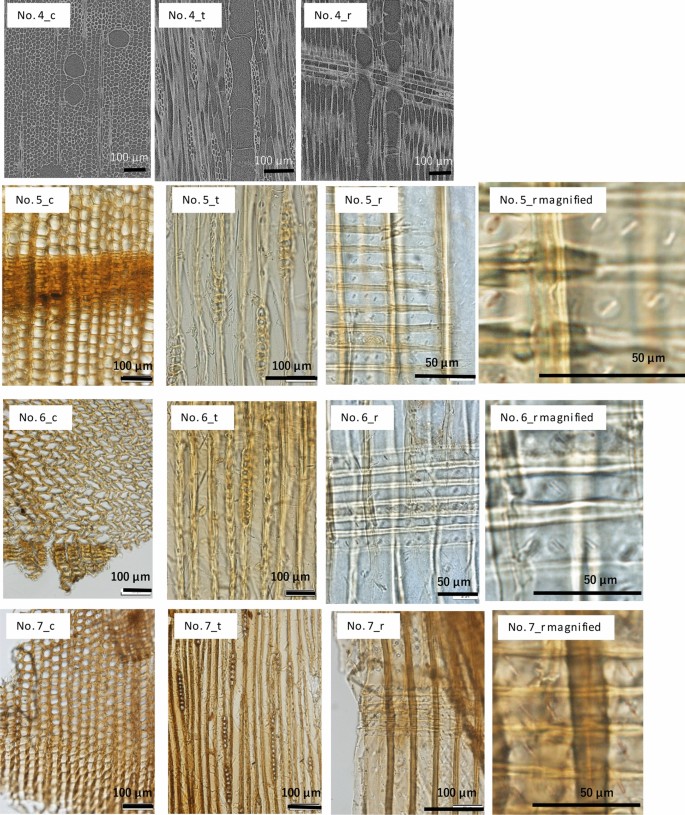

Four samples (Nos. one–four) of the xv samples were too minor and brittle for microscopic preparation. To obtain inner microstructural images safely from these tiny and fragile samples, SRX-ray μCT was applied on the beamline 20XU at SPring-viii, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. Wood samples with a height of 5 mm and a diameter of 0.7 mm were fixed on the cylindrical stick. The sample was scanned with a rotation of 0.ane°, and 1800 projections were acquired using a CCD photographic camera. The resolution of the images was 0.472 µm/pixel. Slide images were and then reconstituted using the free software Image J.

Through image processing with Epitome J software, pseudo-sections were obtained in transverse, radial, and tangential directions, which are necessary for wood identification. Each original reconstituted slice made past SRX-ray μCT was approximately 0.472 μm thick. Therefore, it was necessary to increase the depth information to avoid losing anatomical information. Thus, 24 slices were merged, and approximately 12-μm-thick pseudo-micrographs were obtained. Wood identification was conducted with these reconstructed pseudo-sections using references from previous publications [15, 16]. For identification, we also referred to the Wood Diverseness HSDB network (http://database.rish.kyoto-u.ac.jp/curvation/bmi/Xylarium_net/cai_jiandetabesu.html).

Results

In improver to the results of Nos. one–iii that take been previously reported [7], our investigation showed that the samples Nos. 1–3, 5–xi, and 13–15 were revealed to be Chamaecyparis obtusa, and No. 12 was Cryptomeria japonica. The Chinese statue (No. 4) was revealed to exist Paulownia sp.

Table 1 besides includes data on Nos. 1–3. Pseudo-sections constructed from the SRX-ray μCT dataset from SPring-viii and micrographs for each sample are presented in Fig. 2 (Nos. 1–three are not included in Fig. 2).

Pseudo-sections of Nos. 4_c, 4_t, and 4_r and micrographs for each sample (5–xv). The pseudo-sections are constructed from the SRX-ray μCT dataset from SPring-8. Woods identification results of Nos. ane–3 have already published in the previous report [vii]. Therefore, they were omitted here

The basis of the above identification is as given below.

Chamaecyparis obtusa (Nos. 1–iii, v–11, and thirteen–xv)

The growth ring boundaries were distinct. The transition from earlywood to latewood was gradual. Resin canals were absent, and resin cell was present. The ray height was 3–9 cells, and the ray width was exclusively uni-seriate. Nos. 1–3, 5–eleven, and 13–15 had piceoid to cupressoid pits with circular borders that occurred effectually two per a cantankerous-field (Fig. 2). More often than not, cross-field pits occurred in the vertical heart of cross-fields. The about of the apertures of cross-field pits opened diagonally to vertically. Recently, wood anatomical differences of Japanese species of Cupressaceae were studied to evaluate the possibility of identifying these species [17]. The anatomical features of Nos. 1–3, 5–11, and 13–fifteen described above were consequent with those of Chamaecyparis obtusa described in the paper above [17]. Thus they were identified as Ch. obtusa.

Cryptomeria japonica (No. 12)

More often than not, the transition from earlywood to latewood is abrupt, but the transverse section of No. 12 contains no ring boundaries (Fig. 2), so information technology was hard to confirm. Resin canals were absent. Ray height was 3–5 cells, and ray width was exclusively uni-seriate. The cross-field-pitting type was taxodioid. The number of pits per cross-field was approximately two–iii. Based on these anatomical features, No. 12 was identified every bit C. japonica.

Paulownia sp. (No. four)

The growth band boundaries could not be observed in No. 4, and then it was difficult to obtain information (Fig. ii). Pores were solitary, sometimes in multiples of 2, with an athwart outline. The tangential diameters of the vessels were approximately 100 µm in the transverse section. The perforation plates were simple. Rays were nearly homogeneous and were 2–four cells broad and 5–x cells loftier. The rays were angular and arrow-shaped. Both ends of each ray had a tapered shape. The walls of the constituent cells were relatively sparse. Based on these anatomical features, No. four was identified as a Paulownia sp.

Word

Wood identification of the Japanese and Chinese Buddhist statues endemic by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, was conducted. Xv samples obtained from viii Japanese and one Chinese wooden sculpture were investigated. Of the Japanese samples, 13 were made of Ch. obtusa, and one (the base of the statue) of C. japonica. The Chinese sample was identified every bit Paulownia sp. Namely, all eight statues from Japan were made of Ch. obtusa, whereas the i from China was made of Paulownia sp.

Generally, the inquiry conducted by Jiro Kohara [18] and others, including the Tokyo National Museum and Forest Research and Management Organization, has revealed that the materials used for Buddhist statues in Japan take changed over time. For case, in the sixth century, just after the inflow of Buddhism, "Houkei (Naki) Maitreya" in Koryuji Temple in Kyoto urban center was scientifically revealed to exist made of Cinnamomum camphora (Fifty.) J. Presl. [19]. Nonetheless, in the 8th century, with the introduction of danzō (sandalwood sculpture) from India via Prc, wood species for statues were drastically changed to T. nucifera in Japan. Although there are exceptions, mainstream species for statues were coniferous.

Regarding the style of Japanese sculpture, previous studies of wood species in wooden Buddhist statues have suggested that from the eighth century onward, nearly of the single-block statues were made from T. nucifera. However, with the gradual introduction of the yosegi technique from the mid-Heian flow, the number of statues made of Ch. obtusa began to increase. Although there are many wooden statues made from T. nucifera in the Heian period, T. nucifera tends to exist used more in single-block sculptures. From this perspective, the fact that near of the Japanese Buddhist statues we surveyed in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, were made of Ch. obtusa is an important finding when because their historic period.

1 statue from China was made from Paulownia sp. Previous research on over 60 Chinese wooden statues preserved in several US museums [4,5,6,7] identified the following wood species using a microscope: Paulownia spp. (17 statues), Tilia spp. (sixteen statues), Salix spp. (fifteen statues), and Populus spp. (3 statues). Amongst these statues, virtually of the Buddhist statues made of Paulownia spp. were thought to be made between the tenth to thirteenth centuries. The Chinese statue in the Museum of Fine Arts identified in this survey was assumed to be made in the same period above, namely Song dynasty by the sculpture style, which is consistent with our previous data.

Unlike in China, in Japan, wood belonging to the genus Paulownia is rarely used for Buddhist statues. For instance, just two statues in Yatadera temple and one statue in the Tōshōdaiji temple in Nara Prefecture accept been identified as Paulownia spp. [twenty]. We do not accept enough data to explain why woods of Paulownia spp. was often used in Chinese statues.

Decision

Wood identification of Japanese and Chinese Buddhist statues owned by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, United states, was conducted. From the eight Japanese woods sculptures and i Chinese sculpture, fifteen samples were collected. All Japanese statues were made of Ch. obtusa, ane sample from the base of a Japanese statue was made of C. japonica, and i Chinese statue was made of Paulownia sp.

Recent research has revealed that the species of copse used for wooden Buddhist statues in Japan differ from those in Red china, the country that introduced Buddhism to Nihon, but the reasons for this difference have non notwithstanding been elucidated. Still, the finding that Japanese wood sculpture from the tenth century AD onward fabricated extensive use of Ch. obtusa is an of import slice of data that will assistance u.s.a. make up one's mind the fashion and appointment of sculptures. The use of C. japonica for the pedestal is as well an of import finding for agreement the origin of the Buddha statue, since C. japonica is endemic to Japan. The unmarried Buddha image from Prc was identified every bit Paulownia sp. Unlike in Japan, our previous enquiry has revealed that many Chinese statues are made of Paulownia spp.

In Nippon, woods of Paulownia spp. was used for article of furniture, koto (13-stringed Japanese zither), boxes, and geta (wooden clogs), while in China, information technology was also often used for sculptures. To understand each country'southward criteria of wood use for Buddhist statues, it is necessary to conduct a continuous survey of the remaining Chinese Buddhist statues in Europe and the United States.

This paper simply reports the results of wood identification of Japanese and Chinese wooden Buddhist statues stored in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, with some give-and-take. However, we have decided to publish all these data together because nosotros believe that information technology is important to share them with researchers in diverse interdisciplinary fields. Now, important cultural assets from Japan [21,22,23] and Red china (as observed on each museum'due south website) are carefully stored overseas, and we hope that building cooperative relationships tin lead to the discovery of Buddhist statues with a new meaning in Asian Buddhist art. Continued research is needed to study the species used to brand Buddhist statues in China in the seventh and eighth centuries and understand the significance of haku written in ancient books in Asian countries. Finally, we would like to continue the enquiry without ever forgetting the ethical perspective in cultural property research. We promise that this written report will highlight the written report of East Asian wooden statues, and we will continue our research in the future.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- SRX-ray μCT:

-

Synchrotron X-ray microtomography

References

-

Kaneko H, Iwasa Thousand, Noshiro S, Fujii T (1998) Wood types and fabric choice for Japanese wooden statues of the ancient period particularly the 7th–8th century. Museum 555:3–54

-

Kaneko H, Iwasa M, Noshiro S, Fujii T (2003) Wood types and fabric option for Japanese wooden statues of the ancient flow (specially of the 8th–9th centuries). Museum 583:five–44

-

Kaneko H, Iwasa Yard, Noshiro S, Fujii T (2010) Wood types and material selection for Japanese wooden statues of the aboriginal period, 3: further thoughts on eighth- and 9th-century sculptures. Museum 625:61–78

-

Mertz M, Itoh T (2010) Analysis of woods species in the collection, wisdom embodied—Chinese Buddhist and Daoist sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, pp 216–225

-

Tazuru-Mizuno S (2021) Forest selection for Chinese wood statues preserved in the several museums in the USA. Seizonken Kenkyu 17:58–60

-

Tazuru S, Mertz M, Kinoshita H, Itoh T, Sugiyama J (2021) Woods identification of Chinese Buddhist statues in the Philadelphia Museum of Fine art. Sci Stud Cult Prop 83:107–117

-

Tazuru Southward, Mertz M (2021) Case report of wood identification of Japanese forest statues owned by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA. Bound-8/SACLA research study, vol viii. Springer, Berlin, pp 506–508

-

Mertz Yard, Itoh T (2007) The study of Buddhist sculptures from Nippon and People's republic of china, based on wood identification. In: Douglas JG, Jett P, Winter J (eds) Scientific inquiry on the sculptural arts of Asia Proceedings of the tertiary Forbes symposium at the Freer Gallery of Art. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, pp 198–204

-

Mertz M, Itoh T (2008) Identification des bois de huit sculptures Chinoises et de deux sculptures Japonaises conserves aux Muses Royaux d'art et d'histoire de Bruxelles. Bull Musees Royaux Art Hist Parc Cinquantenaire Brux 76(127–148):217–224

-

Mertz K, Itoh T (2010) A study of the forest species of 73 deity sculptures of the Hunan Province, from the Patrice Fava Collection. Asie xix:183–214. https://doi.org/10.3406/asie.2010.1352

-

Tazuru South, Mertz M (2021) Example study of the forest identification of a Chinese eleven-headed Guanyin Owned by the Cleveland Museum of Fine art. Spring-8/SACLA research report, vol 9. Springer, Berlin, pp 524–526

-

Mizuno South, Torizu R, Sugiyama J (2010) Forest identification of a wooden mask using synchrotron Ten-ray microtomography. J Archaeol Sci 37:2842–2845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2010.06.022

-

Hwang SW, Tazuru Southward, Sugiyama J (2020) wood identification of a historical architecture in Korea by synchrotron Ten-ray microtomography based three-dimensional microstructural Imaging. J Korean Woods Sci Technol 48:283–290

-

Tazuru-Mizuno S, Sugiyama J (2019) Wood identification of Japanese Shinto deity statues in Matsunoo-taisha Shrine in Kyoto by synchrotron 10-ray microtomography and conventional microscopy methods. J Wood Sci 65:threescore. https://doi.org/x.1186/s10086-019-1840-2

-

Wheeler EA, Baas P, Gasson PE (1989) IAWA listing of microscopic features for hardwood identification. IAWA Bull NS 10:219–332

-

Richter HG, Grosser D, Heinz I, Gasson PE (2004) IAWA list of microscopic features for softwood identification. IAWA J 25:1–70. https://doi.org/x.1163/22941932-90000349

-

Shuichi Due north (2011) Identification of Japanese species of Cupressaceae from wood structure. Jpn J Histor Bot 19(one–2):125–132. https://doi.org/x.34596/hisbot.nineteen.1-2_125

-

Kohara J (1972) Kinobunka. Kashima syuppankai, Tokyo, pp 31–114

-

Kaneko H, Noshiro Due south, Abe H, Fujii T, Iwasa G (2019) Reexamination of "Samples formerly owned past Kohara Jiro for a material study of wooden sculptures." Museum 679:5–lx

-

Itoh T, Sano Y, Abe H, Utsumi Y, Yamaguchi K (2011) Useful trees of Japan: a colour guide. Kaiseisya, Otsu, pp eighty–83

-

Shimizu Z (1979) Japanese sculptures in America and Canada (i). Ars Buddhica 126:67–88

-

Shimizu Z (1979) Japanese sculptures in America and Canada (two). Ars Buddhica 127:88–116

-

Shimizu Z (1980) Japanese sculptures in America and Canada (3). Ars Buddhica 128:98–117

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 19K01124, obtained by Suyako Tazuru. Role of this study was supported by the Database for the Humanosphere of RISH, Kyoto University, as a collaborative program. We are indebted to Abigail Hykin (Conservator of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and her colleagues for providing the opportunity to investigate wood sculptures and for their kind cooperation and suggestions. The synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at beamline 20XU at SPring-8 (Japan) with the approving of the Nippon Synchrotron Radiation Research Constitute (JASRI) (Proposal No. 2018B1747). This work was as well supported past Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from JSPS (19K01124) and mission-linked research (mission 5-4) from RISH, Kyoto University. The wood identification results of the Buddhist sculpture of Amida (12.129.1-ii), the Deva statue (12.333), and the Shinto deity Hachiman in the Guise of a Buddhist monk (36.413) were preliminarily presented in the Spring-8/SACLA Research Reports, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2020.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Grants from the Nihon Club for the Promotion of Scientific discipline (KAKENHI, 19K01124 obtained by Suyako Tazuru) and RISH, Kyoto Academy (Mission-linked Research Funding, #2018-5-4-1, #2019-5-4-one, and #2020-5-4-1).

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

ST, MM, TI, and JS have participated sufficiently in forest identification and conduct full responsibleness for this content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Artistic Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits employ, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original writer(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article'south Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the fabric. If material is not included in the article's Creative Eatables licence and your intended use is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will demand to obtain permission direct from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Tazuru, S., Mertz, Thousand., Itoh, T. et al. Wood identification of Japanese and Chinese wooden statues endemic by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Usa. J Wood Sci 68, 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-022-02020-x

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-022-02020-x

Keywords

- Synchrotron X-ray microtomography

- Japanese statues

- Chinese statue

- Wood species identification

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Source: https://jwoodscience.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s10086-022-02020-x

0 Response to "How Were Japanese Fine Arts Different From the Chinese Models?"

Postar um comentário